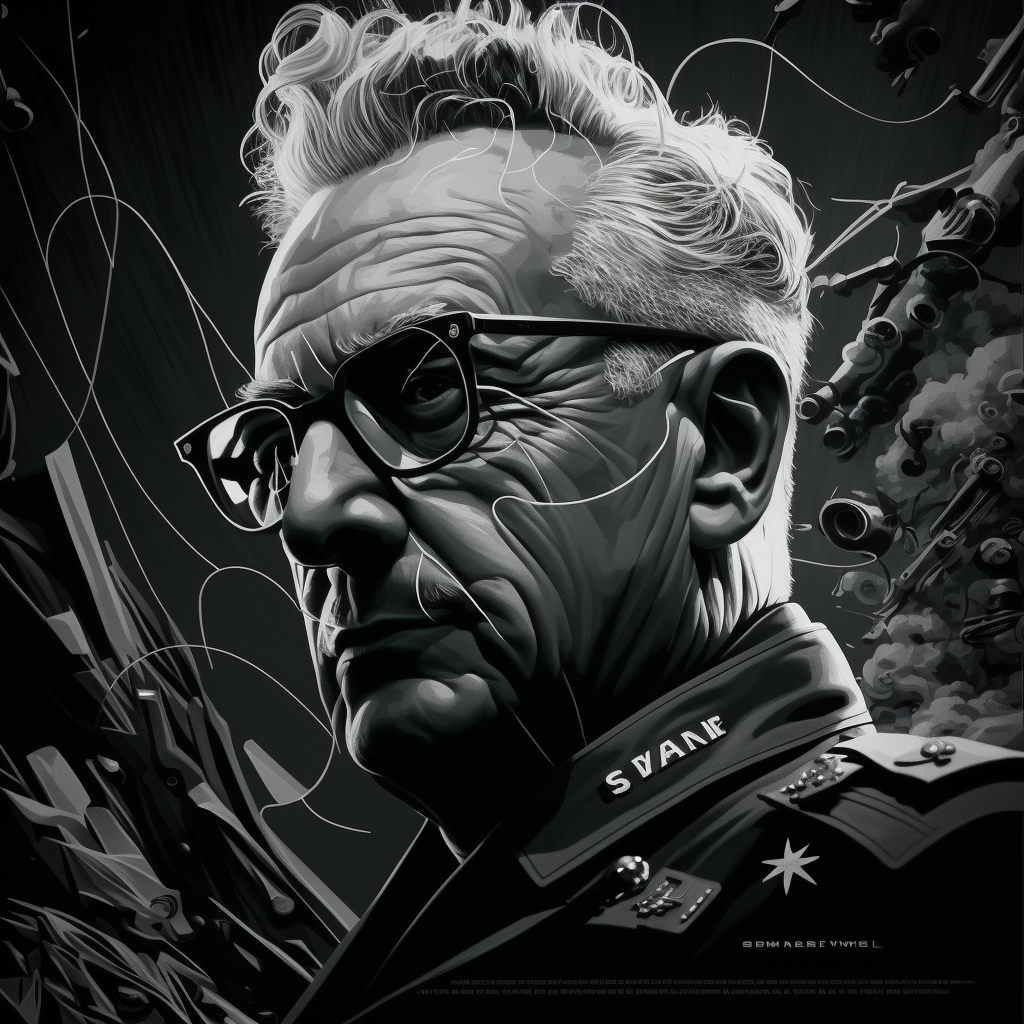

Why Are Fictional Despots So Much More Competent than Real Ones?

How I learned to stop worrying and understand that reality is more like Dr. Strangelove than the Hunger Games.

I learned something interesting this week.

President Tayyip Erdogan, the authoritarian leader of Turkey, believes that the best way to combat inflation is to lower interest rates. This, according to any normal understanding of economics, is the equivalent of proclaiming that up is down or that the Earth is flat. (Year-over-year inflation in Turkey is currently at 50 percent.)

Turkey under Erdogan has become a model of illiberal hybrid democracy—a place where elections still take place but dissent is criminalized, opposition politicians are arrested and detained, protest is suppressed, media outlets are silenced, and voter intimidation is rampant. In 2016, he used a failed coup attempt to consolidate power even further by jailing opponents and purging the military of anyone who might oppose him.

But even with the deck stacked so heavily in his favor, Erdogan, who has kept an iron grip on power for more than 20 years, faces a real challenge on May 14th in what is probably the toughest election in his political career. Fury over the government’s response to the worst earthquake in a century—combined with a widespread feeling that decades-long corruption and lax building-code enforcement made the death toll an order of magnitude worse—has turned the Turkish public against him.

The last thing he needs is to do things that make out-of-control inflation worse. Does he not have any close advisor who can sit him down and explain that his economic policies could amount to electoral suicide?

In fiction, we tend to like our authoritarians to be clever and always one step ahead of the hero until the very end. In the best stories, power-hungry villains are complex, cynical, and sometimes morally conflicted. Much goes on behind the scenes. They don’t believe the stories they tell their followers.

In The Hunger Games, President Snow understands the threat that Katniss Everdeen represents better than she does herself. Cersei Lannister is smarter than anyone else in the Seven Kingdoms. (Cersei Lannister is smarter than all of us.)

In real life, authoritarians lately seem to be blundering into one catastrophe after another. They believe weird things about themselves and others. If anything, it seems like a miracle that they survive as long as they do. Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine was, as Ian Bremmer put it, the

“single biggest geopolitical mistake made by any leader on the global stage since the Wall came down in 1989 … the misjudgment was massive. The failure was immense and immediate. And the consequences for Putin and for Russia will be permanent.”

Couldn’t Putin or anyone else in the Kremlin have foreseen this? Alas, Putin lives in a hermetically sealed information bubble–he reportedly doesn’t even use the internet —which begs the question, how can he even function as the leader of one of the largest countries in the world?

The fact that real-life dictators and their imitators are usually banal, cartoonish, or just weird poses challenges for a fiction writer, especially if your goal is to create a realistic story with tension and menace.

According to Washington insiders, the reality of the Trump administration (no stranger to the occasional authoritarian impulse) was much closer to Veep than House of Cards. (Veep executive producer David Mandel told Politico “they’re either taking from our show or doing their own version of it … it’s the reason we left the air.”)

Is the desire to believe in (and write about) despots who are as cunning as they are evil just the inverse of the belief in a Deep State that secretly controls everything? Maybe it’s just more comforting to believe that someone actually knows what they’re doing. There is something deeply unsettling—and somehow even more unjust—about a bumbling despot, in love with his own cult of personality, who can’t understand basic facts but still manages to stay in power.

I wouldn’t say it’s easy to write a nefarious leader who is cunning, manipulative, and always a step ahead of the hero (it’s not, trust me). But maybe the true test is to create a self-obsessed, sadistic buffoon who nevertheless wields power and isn’t easily brought down.

Thanks for reading Write Imitates Life! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.