Tyranny Gets Personal

How the best show on television illuminates personality-cult capitalism.

Warning: spoilers for Severance ahead.

In the Apple TV show Severance, employees of the mysterious corporation Lumon are given brain implants that split consciousness. The implant takes effect at the beginning of the work day and reverses when they leave in the evening. On the inside, employees experience and remember nothing from their outside life. Outside, they remember and know nothing about their work or anything they experience on the “severed” floor.

The premise is both absurd and relatable. Most of us have at some point held tedious, un-edifying jobs that we try to put out of our minds the minute we clock out and return to our “real” lives. It's bad enough that we're forced to rent out a third of our lives to do work that we hate. Why should we have to be present for it?

The problem is, somebody has to be present, and that somebody is probably pissed.

From Severance Wiki’s description of the first episode:

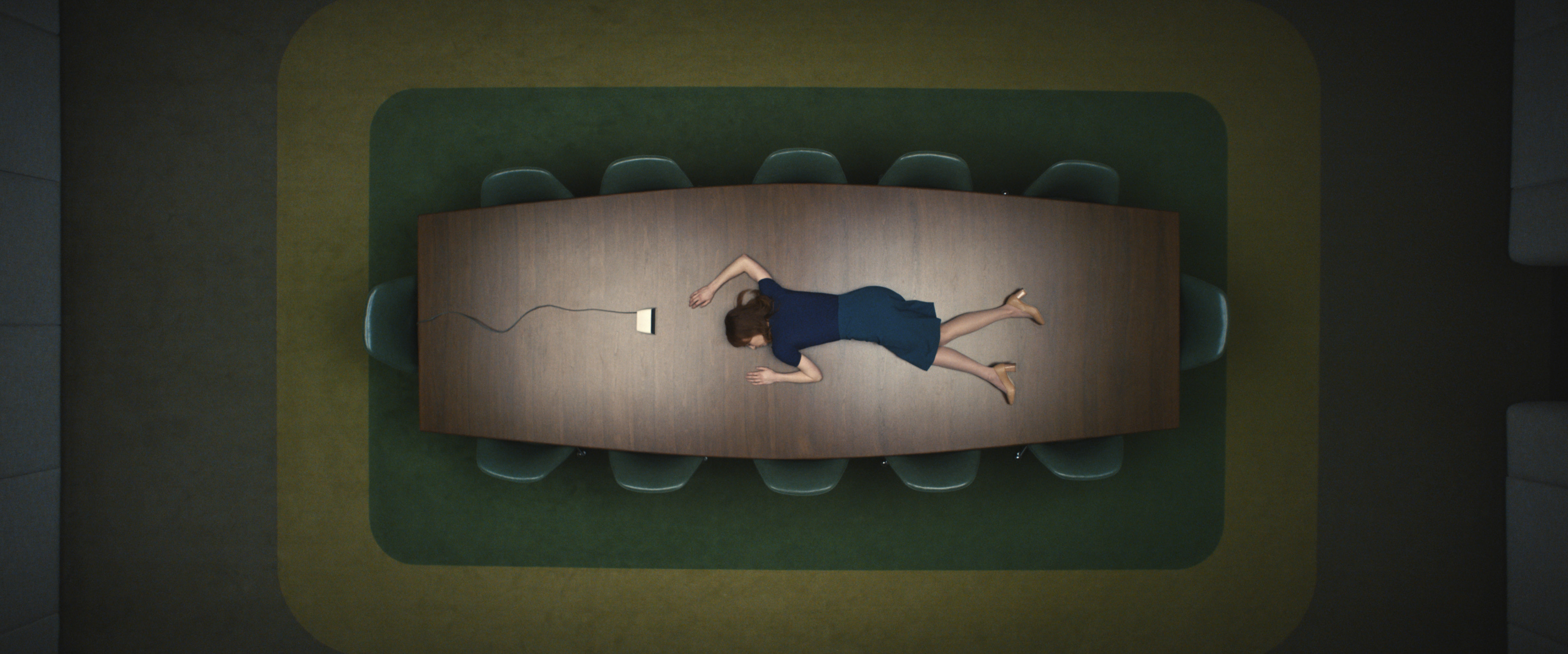

A red haired woman is passed out on top of a large conference table in an otherwise empty room. She is awakened by a voice coming through a small speaker that asks her, “Who are you?”

The voice on the speaker offers, or demands, that she respond to a five-question survey. The woman, although clearly confused, consents to the unseen questioner's prodding. She takes the survey and receives a perfect score, though her answers are mostly “I don't know.”

The survey is administered by Mark S., who we soon learn is the show’s protagonist. Mark tells the woman that her name is Helly R. and tries to put her at ease, but she is agitated. Mark explains that she is applying for a job on the severed floor.

As Mark tells Helly, he, too, once woke up on the conference room table, furious and unable to answer questions about who he was. Eventually, he came to terms with his situation, and now his job is to help Helly come to terms with hers.

Technically, Helly is allowed to leave, but as soon as she steps into the stairwell, she finds that she has returned. Mark explains: "Every time you find yourself here, it’s because you chose to come back."

Reassuring Helly that she is neither dead nor in hell, Mark brings Helly to Ms. Cobel's office where she is given a video on a small disk to watch.

Helly ... sees an image of herself, introducing herself to herself. A version of Helly from about two hours prior reads a statement into a camera, explaining her decision to voluntarily undergo the process colloquially known as “Severance.” The effect of this procedure is that her work life memories and personal life memories are split - a change that is irreversible.

It's a choice most of us are familiar with. You have to earn a living. The person you are outside of work (your “outie”) will continue to force the working you (or your “innie”) to go back, no matter how hard your innie rebels.

It is a choice. Isn't it?

At a superficial level, the severed employees of Lumon Industries represent the ultimate extension of Marx's alienated worker, manifested in cubicle form.

Helly, Mark, and their colleagues Dylan and Irving work in Macrodata Refinement, spending their days moving numbers on a screen into little boxes. (“The work is bullshit,” says Helly. “The work is mysterious and important,” says Mark.)

Employees of the severed floor are alienated from other workers (social relations are strictly controlled) the product of their labor (the literally don't know what they are producing) and from themselves (their humanity is divided).

In this telling, the villain is the system. Even the sinister non-severed characters who work on the floor (Mr. Milchik and Ms. Cobel) are essentially just middle management. The “Board” of the company is faceless and nameless, their instructions disconcertingly relayed and interpreted through their intermediary Nathalie and her bluetooth.

As the story progresses, however, we discover something more disturbing. Behind the corporate veneer lies not just the pursuit of profit but the bizarre utopian visions of the Eagan dynasty.

The setup of the show offers ample opportunities for dramatic irony, leading to one of the best season cliffhangers of modern television as, for a few moments, the “innies” wake up and get a glimpse of what the outside world is like. Among other things, at the end of Season 1, we learn that Helly R. is actually Helena Eagan, daughter of ghoulish CEO Jame Eagan.

Season 2, which just ended, further reveals the extent of Eagans' cult-like grip on both Lumon and the company town of Kier. By the time it’s over, we fully understand that Lumon is more than just a faceless corporation trying to maximize shareholder value: it's a cult of personality, worshipping its late founder Kier Eagan as a Jesus-like figure whose life story and written principles serve as a kind of scripture.

What initially appears to be standard corporate exploitation turns out to be something more insidious. The severed floor isn’t a cost-saving measure or productivity hack—it’s an ideological experiment, a quasi-religious project of remaking humanity in service to a billionaire's messianic delusions.

Sound familiar?

Whether the writers of Severance intended it or not, the show captures a shift from traditional corporate capitalism (impersonal, rules-based, transparently profit-driven) to billionaire cult capitalism (personality-driven, arbitrary, ideologically motivated) and reveals how the second model is emerging from (or perhaps was always hidden within) the first.

The Elon Musks, Mark Zuckerbergs, Peter Thiels, and Sam Altmans of the world are no mere capitalists. They are visionaries, futurists, self-styled saviors of humanity, demanding not just our labor but our obeisance to their drams of colonizing Mars, creating virtual metaverses that transcend the limits of the physical world, submitting to AI, or replacing democracy with a corporate monarchy. In all cases, to question the means is to doubt the mission — and the mission is nothing short of salvation.

When these billionaires claim to be reinventing humanity while treating ordinary people as disposable, they're following the Eagan playbook. Like Lumon's severed workers, the rest of us are prodded, coerced, or forced to submit to the whims, fetishes, and cruelties of oligarchs.

As the country hurtles toward techno-fascism, many are fighting back. I guess we'll have to wait until Season 3 to see who wins.